Self-control Protects Tibetan Adolescent Orphans from Mental Problems: A Mediating Role of Self-esteem

Abstract

Introduction: Orphans who lose their parents for various reasons are usually adopted by eligible families or raised by the government and organizations collectively. Although their basic needs are taken care of, the absence of parents in life makes orphans face higher risks of mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression, leading to lower levels of self-esteem and happiness. Previous studies have shown that self-control may have an effect on improving self-esteem, thus it could become a way to protect mental health. This study would test the effects of self-control on levels of self-esteem and mental wellbeing in a group of Tibetan orphans.

Methods: Participants included 143 adolescents across ages 16 to 22 (Mage = 18.77, 54.8% female) from the orphanages in Tibet. They completed questionnaires assessing self-control, self-esteem, and clinical symptoms (SCL-90-R).

Results: Self-control was negatively associated with psychological illness through improved self-esteem.

Conclusions: Our research suggests that self-control is a protective factor for the mental health of adolescent orphans, which may be achieved by influencing the levels of self-esteem. Limitations and future study directions are discussed.

Keywords: orphan; self-control; self-esteem; mental health; Tibet

1 Introduction

The area of Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, located in Southwestern China, holds the highest number of orphans in proportion to its population (approximately 15.75 orphans in every 10,000 citizens) and the highest institutionalized orphan rate (99.7%) in China according to Ministry of Civil Affairs of China in 2019 (see supplement material). Inhospitable geographical conditions (e.g., average altitude over 4000 meters, lack of oxygen) in this area have led to a lower average life expectancy and a higher accidental mortality rate. At the same time, sociocultural factors also contribute to its high birth rate (14.6%) and natural population growth rate (10.14%), both ranked the highest among all provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, according to China Statistical Yearbook (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2020). Nevertheless, in conformity with local social norms and cultural traditions, most Tibetan people hold against contraception and abortion. Hence, Tibetan people would give birth to children as long as they are pregnant. Moreover, it is worth noting that when accidents occurred to the parents (e.g., getting sick, suffering from accidental injuries) or in the case of unplanned pregnancies before marriage, to a large extent, their children would become orphans and have to go to local orphanages instead of adopted families.

Consequently, as a marginalized group that are often left unprotected in the society, orphans would have to go through a series of complicated life changes while dealing with serious issues like health problem, educational disparities, social exclusion, and psychological distress as they grow up. However, there is a large gap in acknowledging these issues, especially regarding orphans’ psychological wellbeing. More ways to guard them against mental illness remain yet to beaddressed.

Previous research has suggested that orphans are more prone to problems, ranging from the lack of study supplies, access to quality clothes and food, to mistreatment abuse, feeling not loved, and discrimination, in comparison with children under appropriate parental supervision (Dorsey et al., 2015). All these may expose them to potential risks of mental health and behavioral problems. Comparing with non-orphanage children at the same age, orphanaged children were found less happy, more vulnerable to behavioral and emotional problems, such as ADHD, conduct problems, depression, and anxiety; and more likely to inadvertently develop adjustment difficulties as well as other psychosocial or behavioral problems (Kaur et al., 2018; Mostafaei et al., 2012). One of the problems, depression, a common mental health disorder, was found to have an overall prevalence of 36.4% among adolescent orphans (Demoze et al., 2018). A majority of adolescent orphans (95.4%) participated in a study reported that orphans were unhappy, feeling bad about themselves, having below-average mental health status, and unable to handle the challenges and negative feedbacks in life (Ushanandini & Gabriel, 2017). Physical ailments, along with mental disorders, such as problems in the digestive system and sleeping disorder, are also seen among orphans (Shafiq et al., 2020).

Researchers believe that the loss of parents and alienated relationships with new caregivers are key factors that bring about a series of physical and mental health problems. Attachment styles formed during early interactions with the caregivers plays a vital role in the growth of children and have a lasting life-long impact, according to the perspective of social development by John Bowlby's attachment theory (1969). Due to the deprived attachment to parental attention and love, orphans have difficulties in forming a stable and secure attachment style (Atwine et al., 2005; Cluver et al., 2009; Sahad et al., 2018), thus potentially leading to a long-term, negative impact on orphans’ wellbeing (Ntuli et al., 2020).

In addition, Huynh et al. (2019) reported that the experience of growing up at orphanage has a profound impact on orphans’ psychosocial development and later mental health functioning outcomes. Similar results were found in other studies indicating that compared with non-institutionalized children, orphans scored significantly lower on mental health and higher on emotional problems like anxiety, depression, and stress (Atwine et al., 2005; Sahad et al., 2018). A semi-structured interview conducted on orphans in their late adolescence in orphanages reported negative emotional experiences in aspects of loneliness, entrapment, boredom or idleness, deprivation, rejection, and helplessness, which were related to peer discrimination, social isolation, detachment from biological parents, and emotional neglect from the caregivers (Boadu et al., 2020). Unlike adopted orphans, institutionalized orphans are not only deriving from their own identities, but also affected by the environment in orphanages. An investigation pointed out that the numbers of children most care-providers have to look after has exceeded the capacity limit of these care-providers, making it difficult for orphans to attain sufficient care and attention they need (Perkaya, 2017). Furthermore, a cross-sectional study surveyed 191 orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) found out that the highest education of 58% of their care-providers is at senior secondary level (Doku, 2016). Additionally, the repeated daily routines in institutions are boring and put pressures on orphans, making them want to escape despite the fear of the life outside due to limited exposure to society (Boadu et al., 2020). The lack of regular screening for mental illnesses in orphanages also makes orphans more vulnerable to undiagnosed diseases (Ntuli et al., 2020).

While more causes are yet to be discovered, studies focusing on discovering protective factors for orphans’ development and integration into the society are as important. Protective factors have been used to refer to all aspects associated with positive outcomes that could help increase individuals’ resilience when facing risks (Luthar et al., 2003). Most orphans would face a wide range of risk factors in school, community and the society, including discrimination, rejection and social isolation. However, many of them lacked social network, one of the prominent protective factors, to buffer against these risks due to the loss of relationships with their parents or caregivers (Boadu et al., 2020; Tefera & Mulatie, 2014).

Apart from social network, self-control is also regarded as a capacity for changing and adapting oneself to produce a better and more optimal fit with the world (e.g., Rothbaum et al., 1982). It is a protective factor relying more on the individuals rather than others. Several studies have suggested that self-control, the capacity of impulse control, is correlated with a wide range of positive and desirable outcomes as well as psychological wellbeing. Some research has illustrated the relationship between high self-control and high social status, that is, children with greater ability of self-control are more popular in social setups (Maszk, 1999). Also, self-control could help inhibiting unhealthy behaviors (Bogg & Roberts, 2004), promoting healthy interpersonal relationships (Tangney et al., 2004), improving health (Moffitt et al., 2011), and sustaining great mental health status across the life course (Fergusson et al., 2013).

Therefore, the ability of self-control could contribute to a healthier psychological development of orphans, protecting them from mental health problems, and help them build up healthy interpersonal relationships with peers, which could reduce their loneliness and the chance of feeling isolated across orphanhood. In fact, self-control may play a more dominant role in the development of institutional orphans than those who do not, due to the lack of parental supervision and guardianship. However, studies have found that the level of self-control in orphans is actually significantly lower than non-orphanage children of the same age (Ling et al., 2018). Possible reasons are the lack of parental role models and interactions to learn self-control methods. Low social expectations are also somewhat detrimental to the development of self-control.

As for the underlying mechanism of how self-control could benefit psychological wellbeing, self-esteem mayperform a vital role. Self-esteem, generally defined as how the individuals feel about themselves (Rosenberg, 1965), is an essential psychological variable, as it affects many parts of an individual’s life (Kernis, 2003). The formation of self-esteem is usually associated with early social relations and evaluation. Felson and Zielinski(1989) pointed out a reciprocal relationship between self-esteem and parental support to children, in which the supporting behaviors of parents were a possible measure of a child’s self-esteem. Self-esteem is also considered as an indicator of adjustment (Whitley, 1983). Individuals with low self-esteem have weak relations with the society, are generally less happy, and more dissatisfied with themselves (Kahle,1980; Kernis, 2003; Rosenberg, 1965; Sun & Stewart, 2007; Torsheim et al., 2001; Tusaie et al., 2007).

Besides, the stability of self-esteem and self-esteem per se were found to have positive associations with self-control. More specifically, individuals with higher levels of self-control would show higher levels of self-acceptance and self-worth, and these positive views of themselves could sustain across time and circumstances (Lowenstein, 1983; Tangney et al., 2004). That is to say, orphans could maintain their levels of self-esteem through self-control and benefit from it in the long run.

Consequently, helping children who lost their parents to grow up healthily and integrate into the society properly is an important research field of interest. Nevertheless, our literature review indicated that there were few studies investigating the mental health problems of Tibetan orphans. This gap is disconcerting given the paucity of understanding of this population. Although conclusions drawn from existing literature studying orphans from other regions or ethnic groups could be applied to Tibetan orphans, more rigorous studies need to be initiated targeting this unique subgroup.

2 Current Study

There is limited research concerning Tibetan orphans, a unique group. In Tibet, though orphans are growing up in orphanages with sufficient food, clothing and proper accommodation and having access to the same education opportunities as non-orphanage children of the same age, the lack of love and social support would put them at high risk of mental health problems. The present study focused on institutionalized orphans in Tibet, aiming to investigate whether self-control could be a protective factor of mental health for Tibetan orphans and explore the possible role of self-esteem in the association between self-control and mental health. We hypothesized that orphans’ self-control could lead to greater psychological health through the mediating role of self-esteem.

3 Methods

3.1 Procedures and participants

The current study is a part of a larger, ongoing project focusing on the mental health of Tibetan orphans. Tibetan orphans were selected from one orphanage in a city in Tibet. Then, they were invited to pre-arranged classrooms to fill out questionnaires under the supervision of our research assistants, who were available to explain or answer any questions as needed. The questionnaires were digitized into Credamo. Each participant has received a smartphone from research assistants and filled out the survey with it.

The Ethics Committee of Tsinghua University has approved the study. To ensure the strictest compliance to the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, we selected adolescence above 16 as survey participates who could determine whether they would like to participate in a research and choose to withdraw from the study anytime they endure mental discomfort from the research content.

In total, 143 Tibetan orphans aged 16 and over took part in the survey. Eight cases with missing values were excluded from all analyses. Among the valid participants (135 valid cases), 54.8% (74 participants) of them were female, with the ages ranging from 16 to 22 (Mage = 18.77, SD = 1.82).

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Self-control

Self-control was assessed using the 19-item revised Chinese version of Tangney’s Self-control Scale (Tan & Guo, 2008; Tangney et al., 2004). The scale included five subscales: impulse control (e.g., “People would describe me as impulsive.”), healthy habits (e.g., “I have a hard time breaking bad habits.”), temptation resistance (e.g., “Sometimes I can’t stop myself from doing something, even if I know it is wrong.”), work ethics (e.g., “I am able to work efficiently towards long-term goals.”), and entertainment temperance (e.g., “I spend too much money.”). These items were rated on a 5-point scale, anchored from 1 = not at all like me to 5 = very much like me. The total scores of each subscale were computed, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-control. However, three items (“I am good at resisting temptation.”; “People can count on me to keep on schedule.”; “People would say that I have iron self- discipline.”) from the subscale of temptation resistance were challenging for the orphans to understand, given their relatively low literacy of Chinese (they usually use the Tibetan language in their daily lives). Based on the CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) results, these three items were excluded in further analyses. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the scale were .86, ranging from .49 to .76 for the five subscales.

3.2.2 Self-esteem

Self-esteem was assessed using the 10-item well-validated Chinese version of the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Participants rated their levels of self-acceptance (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.”) on a 5-point scale from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”. The total scores were computed and used in analyses, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-esteem. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the scale were .65.

3.2.3 Mental problems

Mental health problems were assessed using the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis & Savitz, 1999). The participants reported their levels of psychological problems and symptoms of psychopathology in the past week on a 5-point scale from 0 = “not at all” to 4 = “extremely”, including nine primary psychiatric symptoms: somatization (e.g., “headaches”), obsessive-compulsive(e.g., “unwanted thoughts, words, or ideas that won’t leave your mind”), interpersonal sensitivity (e.g., “feeling critical of others”), depression(e.g., “feeling low in energy or slowed down”), anxiety (e.g., “trembling”), hostility (e.g., “feeling easily annoyed or irritated”), phobic anxiety (e.g., “feeling afraid to go out of your house alone”), paranoid ideation (e.g., “feeling that most people cannot be trusted”), psychoticism (e.g., “hearing voices that other people do not hear”), and one category of “additional items” assessing other aspects of psychiatric symptoms (e.g., “poor appetite”). Both the total scores and each subscale were computed, with higher scores indicating higher severity of corresponding mental symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the scale were .98, ranging from .70 to .89 for the ten subscales.

3.3 Data Analysis

In order to investigate the impact of self-control on mental problems and the possible mediating role of self-esteem in the path, we conducted structural equation modeling (SEM) using the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012). The five self-control indicators were combined to form the latent term, and the self-esteem indicator was treated as a mediator. All of the primary psychiatric symptoms as well as the additional items assessed by SCL-90-R were included in the model. Considering the potential discrepancy of self-esteem, self-control and mental health among participants of different genders and ages (Bleidorn et al., 2016; Patalay & Fitzsimons, 2018; Zondervan-Zwijnenburg et al., 2020), demographic variables including gender and age were considered as the covariates in the model. To further examine the indirect effect, a bootstrapping resampling procedure with 5000 replications and a 95% confidence interval was used, and confidence intervals that do not include zero indicated significant indirect effects.

We would use the following fit indices to evaluate the model’s goodness of fit: χ2 test (χ2/df ratio of 5 or below), the comparative fit index (CFI; .90 or above), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; .08 or below), and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR; .08 or below).

4 Results

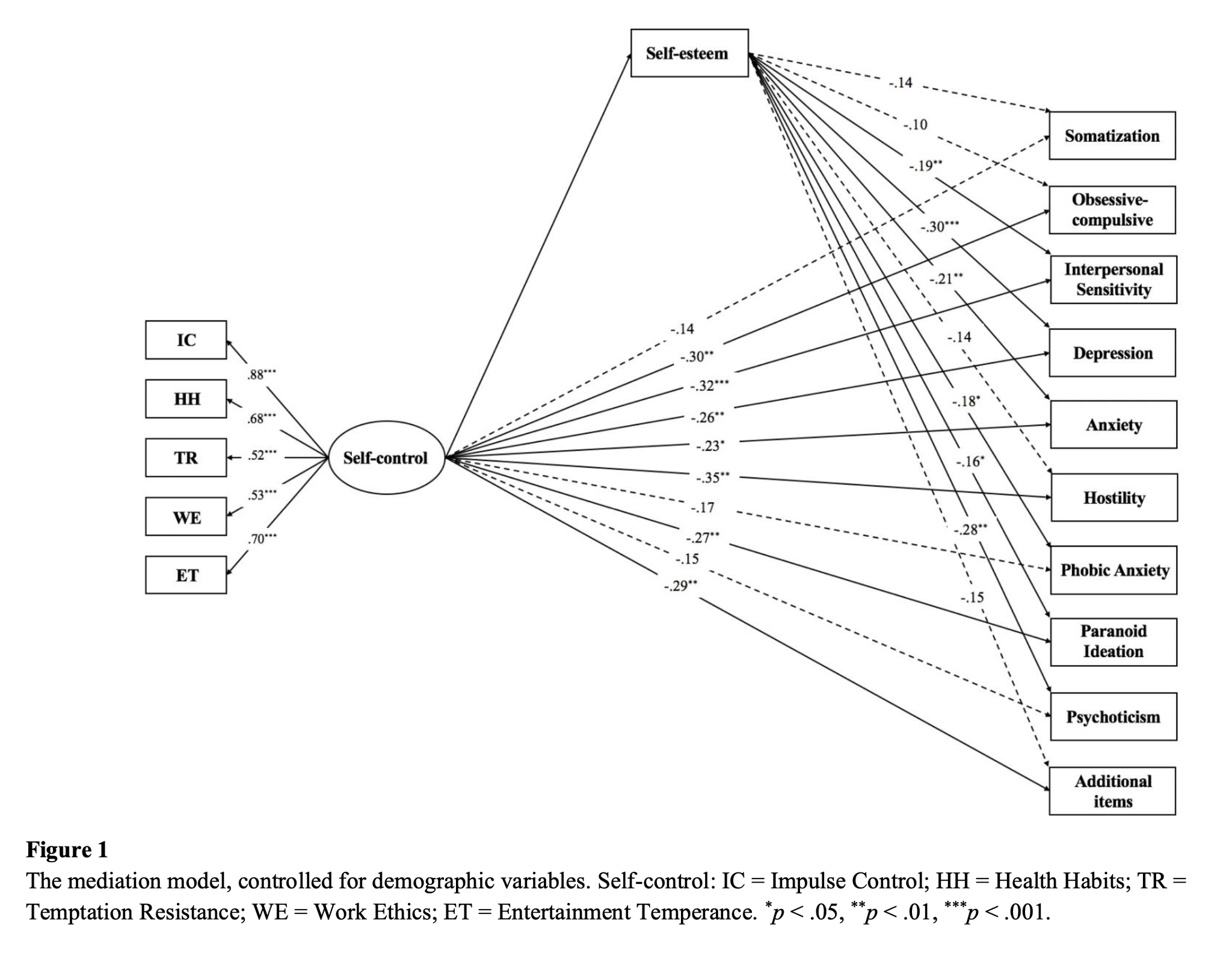

The descriptive statistics for all the variables in the present study were shown in Table 1. Generally, self-control was positively correlated with self-esteem while negatively correlated with psychiatric symptoms. The mediation model was represented in Figure 1. The goodness of fit of the model was acceptable (χ2(59) = 87.20, p = .010, χ2/df = 1.48, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .060, SRMR = .039).

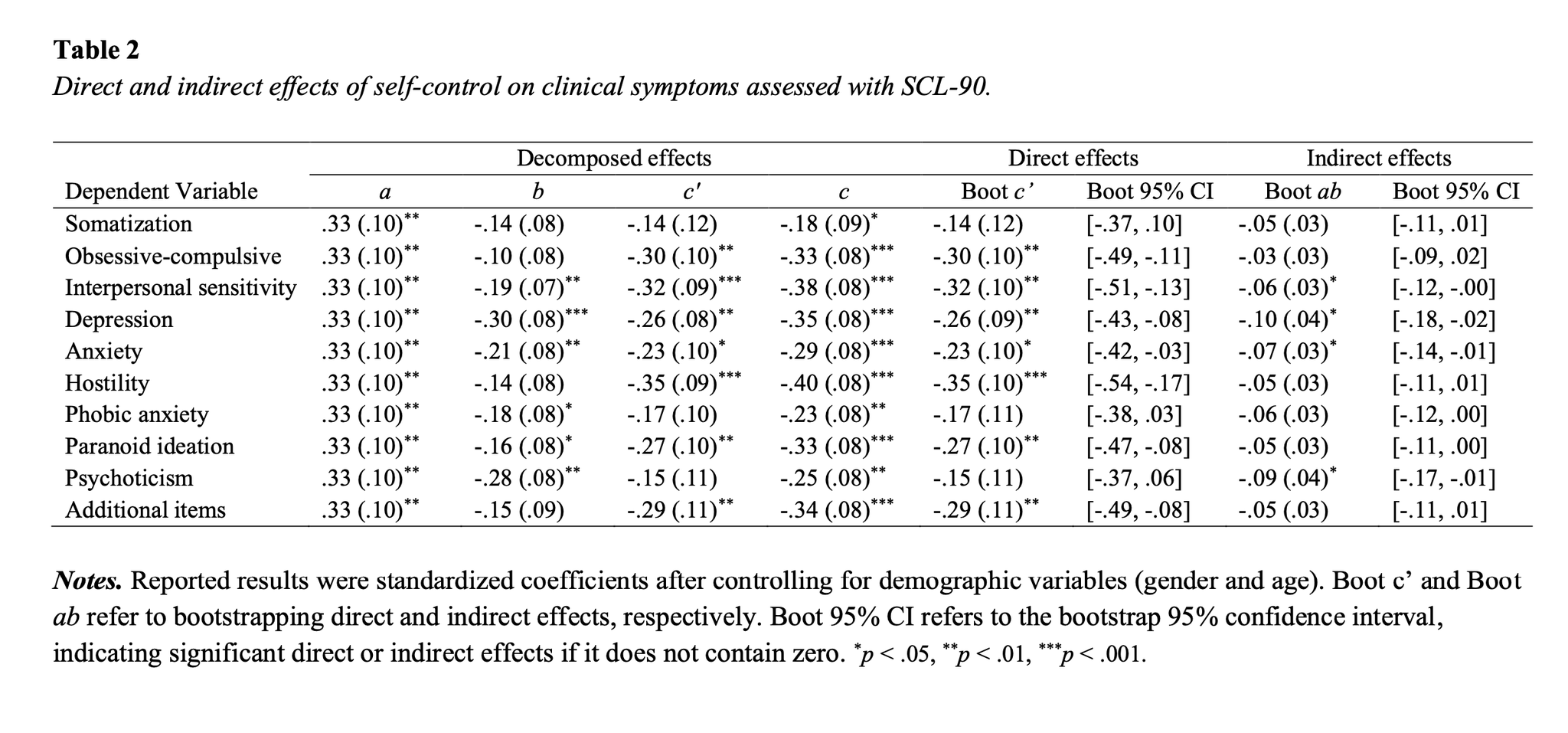

The coefficients of the mediation model were shown in Table 2. More specifically, after controlling for the demographic variables, self-control could positively predict self-esteem (a path; β = .31, p =.004). For the b path, self-esteem was negatively correlated with the severity of interpersonal sensitivity (β = -.17, p = .028), depression (β = -.29, p < .001), anxiety (β = -.20, p = .018), phobic anxiety (β = -.17, p = .046), and psychoticism (β = -.26, p = .002), while it had no independent impact on somatization (β = -.14, p = .117), obsessive-compulsive (β = -.08, p = .362), hostility (β = -.13, p = .126), paranoid ideation (β = -.14, p = .100), and additional category (β = -.15, p = .089). For the c’ path, self-control could negatively predict the severity of obsessive-impulsive (β = -.30, p = .001), interpersonal sensitivity (β = -.31, p < .001), depression (β = -.25, p = .003), anxiety (β = -.22, p = .013), hostility (β = -.35, p < .001), paranoid ideation (β = -.27, p = .002), and additional category (β = -.29, p = .001), while it could not significantly predict the levels of phobic anxiety (β = -.16, p = .068), somatization (β = -.14, p = .142) and psychoticism (β = -.14, p = .111).

The further mediation analysis using bootstrapping resampling procedure suggested that, the indirect effects of the self-control via self-esteem were significant on the severity of some of the clinical symptoms, including depression (Boot ab = -.09, 95% CI [-.16, -.02]), anxiety (Boot ab = -.06, 95% CI [-.14, -.00]), and psychoticism (Boot ab = -.08, 95% CI [-.15, -.01]), as the bootstrap 95% confidence interval did not contain zero. For the other psychiatric symptoms, the mediating role of self-esteem was not significant (the detailed coefficients were represented in Table 2).

5 Discussion

Existing literature revealed that orphans were susceptible to multiple psychological problems. However, few studies have examined the protective factors for orphans that could protect them from potential mental illness. The present research focusing on Tibetan adolescent orphans attempted to investigate the protective effect of self-control and its underlying process. The results indicated that self-control was a significant predictor of Tibetan orphans' mental health and self-esteem could play a mediation role in the relationship between self-control and mental health.

Our study found that self-control was negatively associated with mental illness, especially the level of depression, anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, horror, and paranoia, which was consistent with previous studies (Tangney et al., 2004; Fergusson et al., 2013). A possible explanation is that orphans lack of support from parents, and it is difficult for them to get timely and sufficient care from their caregivers when they go through stressful or other traumatic events, thus making self-control appears to be a key factor for them to handle the psychological problems, including social anxiety and poor social interaction (Akshita & Suvidha, 2016; Sushma et al., 2016). Therefore, self-control, which is considered a key factor for a broad range of personal and interpersonal issues (Tangney et al., 2004), becomes increasingly important when predicting adolescents’ mental health.

Consistent with the previous findings, self-control is positively associated with Rosenberg’s self-esteem (Tangney et al., 2004), a well-designed indicator of self-acceptance without registering inflated views of the self. Tangney (2004) proposed that the focal point to the concept of self-control is the ability to override or change one’s inner responses, interrupt undesired behavioral tendencies, and refrain from acting on them. Individuals with high self-control believe that they are able to cope with challenges in their life (Simon & Schuster, 1997). Similarly, Mazhar (2004) considered self-esteem as a sense of self-recognition as well as the worth and value people endued themselves. Once individuals build a positive self-belief system, they could obtain high levels of self-esteem. In the present study, orphan adolescents who had high self-control exhibited high self-esteem, which is probably because people with high self-control tend to believe in themselves and regard themselves as valuable and precious, and this perception will maintain stable throughout time. As for orphans, a high level of self-control could lead to better regulation of their impulses, external temptations, better management of their health, work, and entertainment, improving the acceptance, and recognition of themselves, thus leading to a high level of self-esteem. The current study also found that orphans who have high self-esteem reported fewer psychological problems, and self-esteem mediates the association between self-control and mental illness. In other words, self-control is a protective factor for orphans’ mental health, which has both direct and indirect effect through self-esteem.

Our study has contributed to exploring protective factors for orphans, providing a theoretical basis for the application of self-control training to the prevention and intervention of psychological problems. Existing evidence has explored the prevalence of mental health problems and psychological distresses among orphans; this study further supplements that self-control may help cope with these issues. Self-control, a trait that can be intervened and changed, is an effective and economical means to improve orphans’ mental health. The study implies a need to raise more awareness and attention from the government and orphanages towards finding therapeutic programs such as mindfulness-based therapies which is exactly the Buddhist tradition derived from their common belief and cognitive behavioral therapies, for orphans to promote self-control and hence improve their mental health and life wellbeing.

Although the current study focused on orphans raised in the orphanage, the results could be applicable to adopted orphans as well. Mohanty and Newhill (2006) found that international adolescent adoptees had a lower level of self-esteem and social adjustment abilities and higher risk of severe mental illness. Thus, as self-control has been shown as a factor to significantly predict self-esteem and social adaptability, it is reasonable to believe that improving self-control will help them deal with the risks of psychological problems.

Several limitations should be noted in this study. First, the sample of present study was all institutionalized Tibetan orphans who were adopted by local welfare centers; thus, it should be cautious when disseminating the results to other orphan groups. Due to the environmental factors and historical traditions in the Qinghai-Tibet area, most of residents there are Tibetans. Studies have demonstrated that historical and cultural background, natural environment, and the form of centralized adoption have great influences on orphans’ mental health state (Luo et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Webb, 2009; Ushanandini, 2017). Future research can continue to explore orphans with other demographic backgrounds and verify the protective effect of self-control on their mental health. Second, only self-esteem was examined in terms of the link between self-control and mental health. This process may be affected by other variables, such as optimism and resilience (Chen et al., 2019; Worku et al., 2018). Therefore, another future direction for this study is to investigate more potential mediators or moderators under the same conditions to better understand how orphans deal with their psychological concerns or distress. Third, all variables were measured using a self-report approach, which might be biased due to social desirability, especially when participants were orphans lacking a sense of security and trust in others (Dontsov et al., 2016; Tadesse et al., 2014). Therefore, more indicators and research methods, such as behavior observations, qualitative interviews, as well as long-term follow-up research, should be taken into consideration in future studies in order to reduce the potential impact of single self-report bias.

Additionally, our study used questionnaires in Chinese, but the participants’ mother tongue is Tibetan. Uneven Chinese proficiency of Tibetan orphans led to misunderstandings of some items in the scale, which were deleted while analyzing the data. Measurement in their native language might be more accurate in assessment of their true mental health state.

Moreover, this study did not control the early experiences of orphans, such as when and how they became orphans. Recalling early traumatic experiences can easily lead to psychological discomfort and emotional fluctuations, so we did not ask the participants about their early experiences, although this might have an important impact on ourresearch. In the future, studies could learn more about each orhpan’ early experience and try to control this variable; that will help us understand how different ages and different forms of bereavement affect an individual’s mental health.

Furthermore, taking the unique natural environment (e.g., unpolluted air, harmonious relationship between local residents and the nature and abundant wildlife etc.) of the Qinghai-Tibet area into consideration, a topic stemmed from this study could be learning how nature relatedness has influenced Tibetan orphan’s psychological health and wellbeing (Nisbet et al., 2011; Zelenski & Nisbet, 2012). Studies have shown that air quality, living conditions and temperature are all important factors affecting individual mental health and wellbeing (Dasgupta, 2001). Additionally, in Tibetan tradition, people generally believe the existence of reincarnation and afterlife, and honor the cultural norms of care and non-killing, which might have a protective effect on their mental health, according to the research conducted by Khenpo (2011). Therefore, how to explore the psychological development of orphans based on the natural conditions and the cultural traditions of the Qinghai-Tibet area is a topic worth further exploration.

Despite having these limitations, our study is still a meaningful attempt. The psychological health of orphans in Qinghai-Tibet area is a crucial topic because mental health enhances individual wellbeing. Nonetheless, due to the extreme natural conditions and other factors, as far as we know, there is still a large gap in research in this field.Especially for Tibetan orphans, promoting their mental health is what researchers should pay attention to. Although the current study was still at the preliminary stage and only verified the hypothesis of the protection path of “self-control-self-esteem-mental health”, it has provided a new perspective in the studies of orphans’ mental status and is filling the gap in the psychological research field on this unique group of orphans.

References

[dataset] National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2020). 2020 China Statistical Yearbook. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2020/indexch.htm

Atwine, B., Cantor-Graae, E., & Bajunirwe, F. (2005). Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine, 61(3), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018

Bleidorn, W., Arslan, R. C., Denissen, J. J., Rentfrow, P. J., Gebauer, J. E., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2016). Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross-cultural window. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(3), 396-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000078

Boadu, S., Osei-Tutu, A., & Osafo, J. (2020). The Emotional experiences of children living in orphanages in Ghana.Journal of Children's Services, 15(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/jcs-10-2018-0027

Bogg, T., & Roberts, B. W. (2004). Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: a meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), 887-919. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887

Chen, Y., Su, J., Ren, Z., & Huo, Y. (2019). Optimism and Mental Health of Minority Students: Moderating Effects of Cultural Adaptability. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2545. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02545

Cluver, L., Fincham, D. S., & Seedat, S. (2009). Posttraumatic stress in AIDS-orphaned children exposed to high levels of trauma: The protective role of perceived social support. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(2), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20396

Dasgupta, P. (2001). Human well-being and the natural environment. Oxford University Press.

Demoze, M. B., Angaw, D. A., & Mulat, H. (2018). Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression among Orphan Adolescents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Psychiatry Journal, 2018, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5025143

Derogatis, L. R., & Savitz, K. L. (1999). The SCL-90-R, brief symptom inventory, and matching clinical rating scales. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 679–724). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Doku, P. (2016). Reactive Attachment Disorder in Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) Affected by HIV/AIDS: Implications for Clinical Practice, Education and Health Service Delivery. Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior, 4(278). doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000278

Dontsov, A. I., Perelygina, E. B., & Veraksa, A. N. (2016). Manifestation of Trust Aspects with Orphans and Non-Orphans. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 233, 18-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.117

Dorsey, S., Lucid, L., Murray, L., Bolton, P., Itemba, D., Manongi, R., & Whetten, K. (2015). A Qualitative Study of Mental Health Problems among Orphaned Children and Adolescents in Tanzania. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(11), 864-807. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000388

Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2013). Childhood self-control and adult outcomes: Results from a 30-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(7), 709–717. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.008

Huynh, H. V., Limber, S. P., Gray, C. L., Thompson, M. P., Wasonga, A. I., Vann, V., Itemba, D., Eticha, M., Madan, I., ... & Whetten, K. (2019). Factors affecting the psychosocial well-being of orphan and separated children in five low-and middle-income countries: Which is more important, quality of care or care setting?. PLoS One, 14(6), e0218100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218100

Kahle, L. R., Kulka, R. A., & Klingel, D. M. (1980). Low adolescent self-esteem leads to multiple interpersonal problems: A test of social-adaptation theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 496–502. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.496

Kaur, R., Vinnakota, A., Panigrahi, S., & Manasa, R.V. (2018). A descriptive study on behavioral and emotional problems in orphans and other vulnerable children staying in institutional homes. Indian J Psychol Med., 40(2), 161-168. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_316_17

Kernis, M. H. (2003). Toward a conceptualization of optimal self-esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 14(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1401_01

Khenpo S. Z. (2011). The Path: A Guide to Happiness. Wisdom Publications.

Ling, Z., Zou, Y., Guo, X., Qiu, Z., & Liu, X. (2018). Relationship among the health-compromising behaviors, self-esteem and self-control of orphans. International Journal of Psychiatry and Neurology, 7(2), 23-30. https://doi.org/10.12677/IJPN.2018.72004

Lowenstein, L. F. (1983). Developing self-control and self-esteem in disturbed children. School Psychology International, 4(4), 229-235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034383044007

Luo Y., Zheng P., Wang Z., Chen Y., Yao X. (2020) Plateau Environment’s Effects on College Students Psychological Health Conditions. In: Long S., Dhillon B. (eds) Man–Machine–Environment System Engineering. MMESE 2019. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, vol 576. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8779-1_76

Luthar, S. S., & Zelazo, L. B. (2003). Research on resilience: An integrative review. In S. S. Luthar (Ed.), Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities (p. 510–549). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511615788.023

Maszk, P., Eisenberg, N. G., & Guthrie, I. K. (1999). Relations of children’s social status to their emotionality and regulation: A short-term longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45(3), 468–492. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23092582

Mazhar, U. (2004). Self-esteem in human development foundation. Retrieved from http://www.yespakistan.com/wel...

Moffitt, T. E., Arsenault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., Houts, R., Poulton, R., Roberts, B. W., Ross, S., Sears, M. R., Thomson, W. M., & Caspi, A. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2693–2698. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010076108

Mohanty, J., & Newhill, C. (2006). Adjustment of international adoptees: Implications for practice and a future research agenda. Children and Youth Services Review, 28(4), 384-395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.04.013

Mostafaei, A., Aminpoor, H., & Mohammadkhani, M. (2012). The comparison of happiness in Orphanage and non-orphanage children. Ann Biol Res, 3(8), 4065-4069. Retrieved from https://www.scholarsresearchlibrary.com/articles/the-comparison-of-happiness-in-orphanage-and-nonorphanage-children.pdf

Nisbet, E.K., Zelenski, J.K., & Murphy, S.A. (2011). Happiness is in our Nature: Exploring Nature Relatedness as a Contributor to Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 303-322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9197-7

Ntuli, B., Mokgatle, M., & Madiba, S. (2020). The Psychosocial Wellbeing of Orphans: The Case of Early School Leavers in Socially Depressed Environment in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. PLoS ONE 15(2), e0229487. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229487

Patalay, P., & Fitzsimons, E. (2018). Development and predictors of mental ill-health and well-being from childhood to adolescence. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(12), 1311-1323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1604-0

Perkaya. (2017). Terengganu Orphan Welfare Organization. Terengganu.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1-36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J. R., & Snyder, S. S. (1982). Changing the world and changing the self: A two-process model of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 5–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.5

Sahad, S. M., Mohamad, Z., Shukri, M. M. (2018). Difference of mental health among orphan and non-orphanadolescents. International Journal of Academic Research in Psychology, 5(1), 556-565. http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARP/v5-i1/3492

Shafiq, F., Haider, S. I., & Ijaz, S. (2020). Anxiety, Depression, Stress, and Decision-Making Among Orphans and Non-Orphans in Pakistan. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 313–318. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s245154

Sun, J., & Stewart, D. (2007). Age and gender effects on resilience in children and adolescents. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 9(4), 16-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2007.9721845

Tadesse, S., Dereje, F., & Belay, M. (2014). Psychosocial wellbeing of orphan and vulnerable children at orphanages in Gondar Town, North West Ethiopia. Journal of public health and epidemiology, 6(10), 293-301. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPHE2014.0648

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

Tefera, B., & Mulatie, M. (2014). Risks, protection factors and resilience among orphan and vulnerable children (OVC) in Ethiopia: Implications for intervention. International Journal of Psychology and Counselling, 6(3), 27-31. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJPC2013.0241

Torsheim, T., Aaroe, L. E., & Wold, B. (2001). Sense of coherence and school-related stress as predictors of subjective health complaints in early adolescence: interactive, indirect or direct relationships?. Social science & Medicine, 53(5), 603-614. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00370-1

Tusaie, K., Puskar, K. & Sereika, S.M. (2007). A predictive and moderating model of psychosocial resilience in adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 39(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00143.x

Ushanandini, N., & Gabriel, M. (2017). A Study on Mental Health among the Adolescent Orphan Children Living in Orphanages. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 7(17), 187-190.

Wang, J., Zhou, Y., Liang, Y., & Liu, Z. (2020). A Large Sample Survey of Tibetan People on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau: Current Situation of Depression and Risk Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 289. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010289.

Webb, D. (2009). Subjective wellbeing on the Tibetan plateau: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(6), 753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9120-7

Whitley, Bernard E. (1983). Sex role orientation and self-esteem: A critical meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(4), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.4.765

Worku, B. N., Abessa, T. G., Franssen, E., Vanvuchelen, M., Kolsteren, P., & Granitzer, M. (2018). Development, social-emotional behavior and resilience of orphaned children in a family-oriented setting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(2), 465-474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0908-0

Zelenski, J.M., & Nisbet, E.K. (2012). Happiness and Feeling Connected: The Distinct Role of Nature Relatedness. Environment and Behavior, 46(1), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512451901

Zondervan-Zwijnenburg, M. A. J., Richards, J. S., Kevenaar, S. T., Becht, A. I., Hoijtink, H. J. A., Oldehinkel, A. J., Branje, S., Meeus, W., & Boomsma, D. I. (2020). Robust longitudinal multi-cohort results: The development of self-control during adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 45, 100817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100817